英国戏剧史及其对英国文学的影响

THE HISTORY OF BRITISH DRAMA AND ITS INFLUENCE ON BRITISH LITERATURE

(作者简介:Eric L 机构特聘文学研读课程,批判性阅读和写作课程高级金牌外教。拥有创意写作和英语文学博士学位,在美国担任大学英语系教授近20年,同时担任多家著名网站专栏作家,著有自传体散文集‘THE WINTERS OF MY SUMMER AFTERNOONS’)

(中文译本, 由机构中英翻译组Wendy W博士翻译)

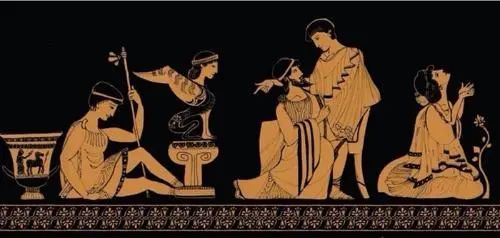

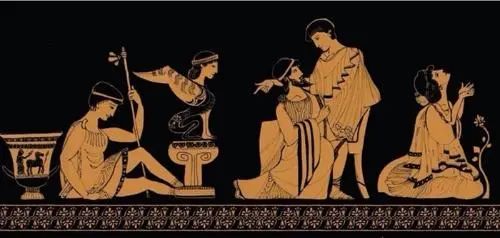

我们现在所说的“戏剧”(drama)(有些人称之为‘舞台剧’(theatre),尽管它们并不完全相同)的根源可以追溯到几千年前,在任何可以被模糊地称为“文学”的东西出现之前。

也许,就像跳舞和吟唱(唱歌的前体)一样,模仿艺术是最早扎根于人类心灵的表达形式之一。我们应该始终牢记,戏剧表演本质上是讲故事。就像洞穴墙壁上的图画是讲故事一样,我们完全可以认为,最早的身体摇摆和以声传意的仪式也是在讲故事。

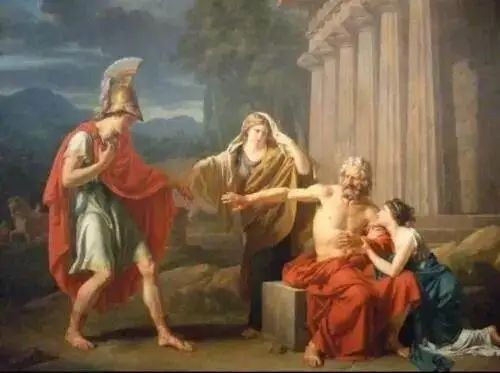

现代舞台表演的前身始于古希腊人。他们伟大的剧作家埃斯库罗斯、索福克勒斯和欧里庇得斯的作品,今天我们仍然可以欣赏——作为表演——当然更多地是以书面形式供学者研究。

很久以后,在中世纪的欧洲,那时候的模仿或表演经常在教堂举行,主要是表现美德和恶习,因此可以被贴上寓言的标签。表演中的人物往往体现出谨慎、耐心、懒惰、贪婪等性格特征。最重要的是,它们的价值在于传教,将基督教的价值观灌输给观众。

教堂外的宗教戏剧表演开始于 12 世纪的某个时候,在此期间,较短的仪式戏剧被合并为较长的戏剧,这些戏剧被翻译成白话并由外行表演。“白话”的意思是他们将“剧本”改编成当地的方言,可以被该特定地区的人们理解和观赏。不用说,这些都没有被写成任何可以被持久传播的形式。

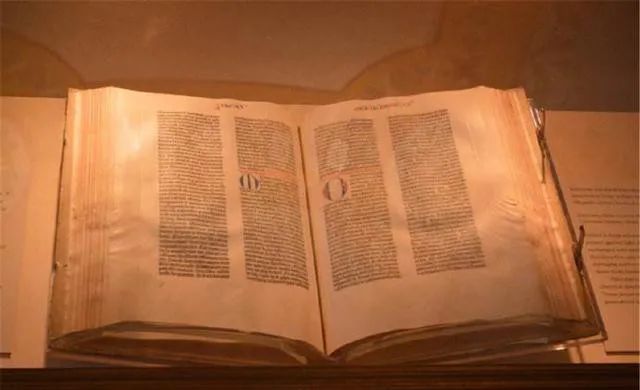

中世纪晚期是舞台剧发展的重要时期,因为那时候经济和政治变化引起了城镇的形成和发展。在不列颠群岛,中世纪有大约 127 个不同的城镇制作了各种戏剧。这一时期最重要的戏剧可能是《普通人》,讲述了一个试图逃离死亡但最终与死亡和解的人的故事。这是它在早期印刷版本中的样子:

EVERYMAN

Here beginneth a treatise how the High Father of Heaven sendeth death to summon every creature to come and give account of their lives in this world, and is in manner of a moral play.

MESSENGER

I pray you all, give your audience,

And hear this matter with reverence,

By figure of a moral play.

The Summoning of Everyman called it is,

That of our lives and ending shows

How transitory we be all day.

This matter is wondrous precious

But the meaning of it is more gracious

And sweet to bear away. The story saith:

Man, in the beginning

Look well and take good heed to the ending,

Be you never so gay!

Ye think sin in the beginning full sweet,

Which in the end causeth the soul to weep

When the body lieth in clay.

Here shall you see how Fellowship and Jollity,

Both Strength, Pleasure and Beauty,

Will fade from thee as flower in May;

For ye shall hear how our heavenly King

Calleth Everyman to a general reckoning.

Give audience and hear what He doth say.

这些台词是由真正的演员在舞台上表演的,但我们有了可以阅读的印刷版,因此,戏剧和文学的融合开始了。

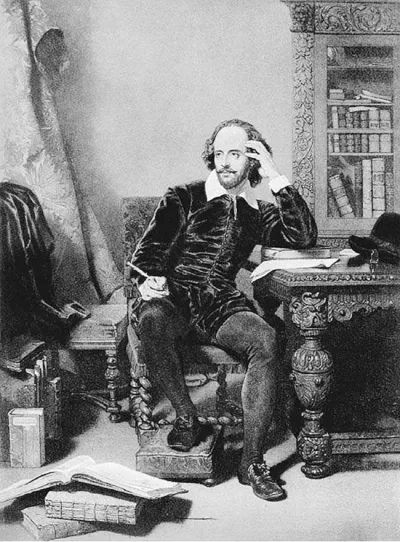

《普通人》(作者不详)与传说中的英国伊丽莎白时代的后期作品几乎没有相似之处。伊丽莎白时代后期,莎士比亚、琼森、马洛和基德等大师编写了舞台剧脚本。虽然他们并没有特意要为后代留下记录,但这些作品集都幸存了下来,并且现在人们研读它们和表演它们一样频繁,这是因为它们也适合被阅读,在某些情况下,它们对现代学术的贡献更多在于作为书面阅读文件的价值,而不是作为戏剧表演——也就是说,无论它们是否被在舞台上表演,它们都是文学。

有多少现代文学学生努力研读哈姆雷特、李尔王和奥赛罗等莎士比亚作品中的雄伟台词,却从未真正看过这些戏剧表演?(可能实际数字比愿意承认这一点的人更多!)

当然,这些表演可以对生活有巨大的影响力:哈姆雷特王子忧心忡忡并试图绘制他的复仇路线,但是他又犹豫彷徨;李尔和奥赛罗愤怒暴躁;无辜的苔丝狄蒙娜被处死;麦克白夫人发动她野心勃勃的谋杀计划——这些都值得观赏。但也没有人能否认马洛和莎士比亚同时也是伟大的诗人。莎士比亚以其十四行诗和戏剧而闻名,而马洛的伟大诗篇“和我一起生活,做我的爱人,我们将证明所有的快乐......”(《热情的牧羊人对他的爱》)今天仍然在婚礼上被朗诵。

伊丽莎白一世

英国戏剧要感谢伊丽莎白一世女王。在她为戏剧捧场之前,戏剧表演并不受尊重,演员被认为是流浪汉和恶棍,与后来几个世纪的马戏表演者没什么不同。他们会从一个城镇来到另一个城镇,搭建既没有道具也没有任何背景的即兴舞台,演员(他们都是男人,因为女性不允许参加表演,会被认为非常不淑女)就这样开始表演。表演通常是淫秽低俗的,但也有戏剧性和打斗的情节(尽管舞台背景需要想象,他们仍然会进行大量没怎么编排过的,暴力的剑斗,在此过程中经常有演员会受伤),然后演员们向观众收取报酬,拆除舞台,扔下几罐啤酒,前往下一个站点。这样的生活虽然很艰难,但他们也总有观众。当然,教会讨厌他们。之后当清教徒在奥利弗·克伦威尔时期统治英格兰时,这种表演并不被他们容忍。

如果不是由于伊丽莎白和她的枢密院,英国剧院永远不会写出这样的台词(克里斯托弗·马洛, 《浮士德博士》——(浮士德博士)化身帕里斯谈论海伦和特洛伊战争:

“Was this the face that launch'd a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss.

Her lips suck forth my soul: see where it flies!

Come, Helen, come, give me my soul again.

Here will I dwell, for heaven is in these lips,

And all is dross that is not Helena.”

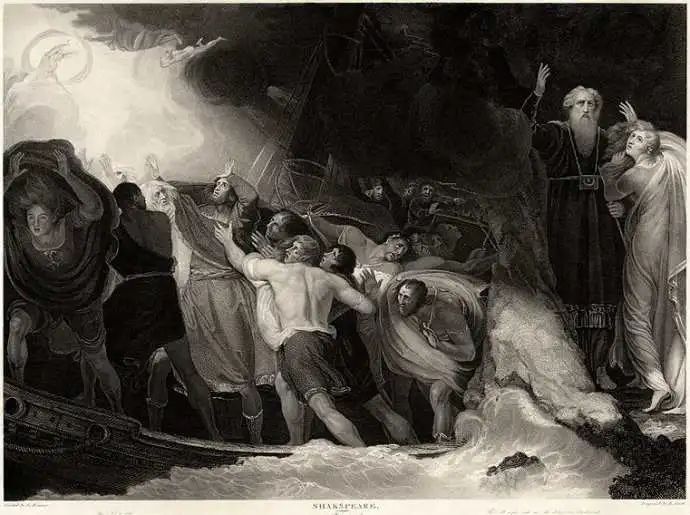

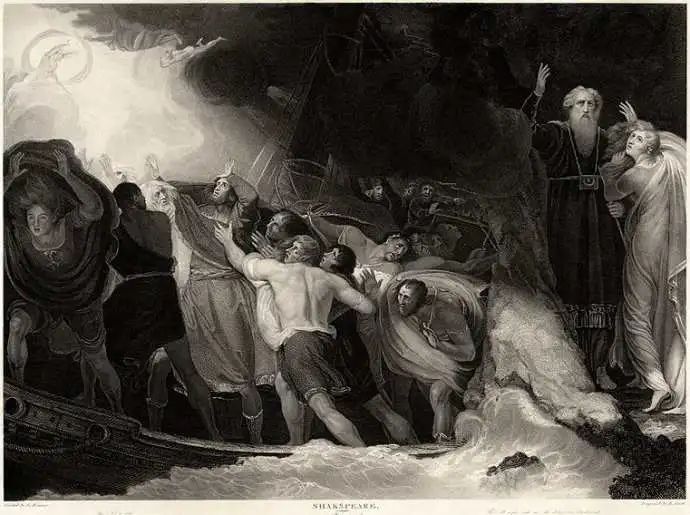

也不会有莎士比亚在《暴风雨》中告别剧院时的这些美丽而难以捉摸的话语:

Prospero speaks to Ferdinand and Miranda

“You do look, my son, in a moved sort,

As if you were dismay'd: be cheerful, sir.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp'd towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Ye all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. Sir, I am vex'd;

Bear with my weakness; my, brain is troubled:

Be not disturb'd with my infirmity:

If you be pleased, retire into my cell

And there repose: a turn or two I'll walk,

To still my beating mind.”

这一切,不言而喻,在舞台上可以完美呈现,但是,有洞察力的人,都能看出语言中的威严与美。因此,戏剧就是文学的动作体现。大多数没有直接在伊丽莎白女王面前演出的戏剧都是在伦敦城门外一个叫做南华克的地方上演的。这样一来,要关闭大都市内剧院的清教徒法就拿他们没办法了。

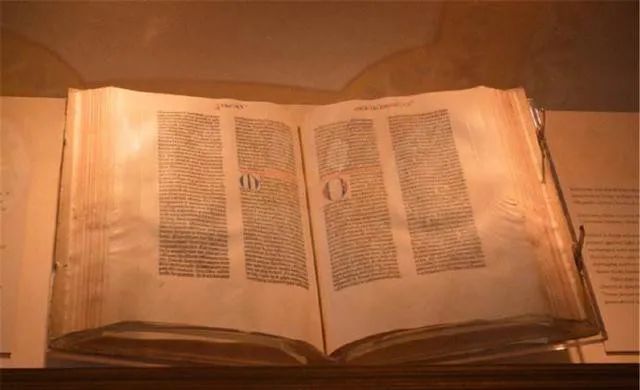

几个重要的历史事件促进了戏剧的发展,从而使它载入了真正的文学史册。第一个是约翰内斯·古腾堡于 1450 年发明了印刷机;第二个是约翰.威克里夫(后来因“异端邪说”被处以火刑)决定将圣经从拉丁文翻译成英文,以便人们可以自己阅读上帝的话,而不必依赖自私富有的主教和红衣主教对圣经进行有利于他们自己的解释。

这些事件之所以如此重要,是因为一方面印刷品得以广泛传播,另一方面(在威克里夫的例子中),整个基督教世界中最重要的一本书突然普及(尽管事实并不那么简单,因为大众中存在大量文盲民众,以及部分天主教会的凶猛抵抗)。我们可以断定,如果没有印刷术,莎士比亚的所有作品都会被遗失。因此,由于文学作品的广泛传播成为了可能,华美的舞台上的台词从此可以被文字记录下来且代代相传。

然而当英国国王被废黜后,在奥利弗·克伦威尔以及清教徒的“圆头党”(由于他们明显的剪短了的头发)当权的“护国公”时代, 戏剧的发展遭受到了重大挫折。

1649 年查理国王被斩首之后,随之而来的是一段漫长的宗教狂热,这意味着剧院的暂时消亡。人们不难注意到,虽然基督教产生了一些世界上最伟大的艺术和文学,但充斥在基督教中并占主导地位的那些严峻、狭隘和狂热的元素,却造就了残暴、迷信和愚蠢的种种行为(奥林匹克运动会被禁了一千年,因为基督徒决心将这种“异教”从他们中间驱逐出去)。所以克伦威尔时期,戏剧一直走下坡路,直到克伦威尔去世,护国公时代结束,新国王复位。

新国王复辟之后,尽管由议会而不是国王或王后主管演出(至今仍然是这样),舞台又回归了,但是(这段时间的戏剧)与文学并没有什么太大的关联。新古典主义时期的戏剧着重华丽,是一种人为的试图恢复罗马时期辉煌的尝试。大部分的文字和绘画也是端庄唯美的。因此,直到 19 世纪中后期,我们才再次看到戏剧与文学的美满结合。

英国戏剧经历了乔治·萧伯纳、奥斯卡·王尔德、约翰·高尔斯华西、威廉·巴特勒·叶芝和哈雷·格兰维尔·巴克的作品的复兴。与他们同时代的大多数阴郁而严肃的作品不同,萧伯纳和王尔德主要创作喜剧。爱德华时期的音乐喜剧非常受欢迎,吸引了‘快乐的90 年代’的中产阶级的注意,也迎合了第一次世界大战期间公众对逃避现实的娱乐方式的偏好。

之前提到的那些作家,尤其是叶芝、萧伯纳和王尔德,文学作品比比皆是,叶芝(他是爱尔兰人,萧伯纳也是)被认为是 20 世纪最伟大的诗人。

近代以来,戏剧变得越来越具有实验性,可以说,许多剧本本身并不像文学作品那样令人兴奋,因为阅读它们并不能像观看舞台上的表演那样让人感受深刻。塞缪尔·贝克特《等待戈多》和英国人汤姆斯·托帕德的作品就是很好的例子。好吧,我们生活在极简主义时代,大多数伟大的剧本都是这样,没有以前的聪明的辩解和妙语连珠。

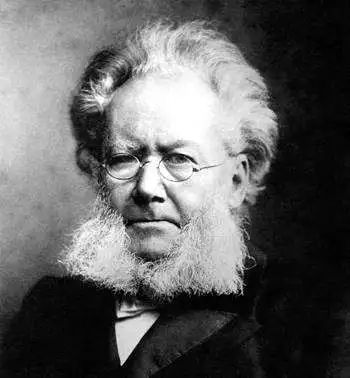

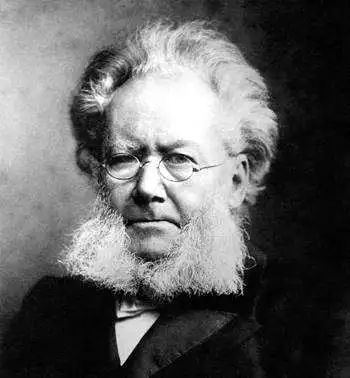

亨利克·易卜生

最后,可以说英国和全世界的舞台都受到了俄罗斯契可夫和挪威剧作家亨利克·易卜生等伟大文学作家的影响。在美国,阿瑟·米勒的《推销员之死》彻底改变了戏剧。爱德华·阿尔比的大部分作品《动物园故事》和《谁害怕弗吉尼亚·伍尔夫》都既是优秀的文学作品,又是伟大的戏剧剧本。T.S.艾略特是公认的有史以来最伟大的诗人。他出生在美国,但后来移居英国并成为皇室臣民。他的关于圣托马斯·贝克特殉难的《大教堂谋杀案》同样是一部文学杰作。

世界获得文学作品的同时,也获得了宏伟的戏剧,比如莎士比亚本人作品的台词:

“To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover'd country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.”

毫无疑问的,从此以后,是戏剧和文学的最好的时代。

英文原文

THE HISTORY OF BRITISH DRAMA AND ITS INFLUENCE ON BRITISH LITERATURE

By Eric L

The roots of what we now call ‘drama’ (some call it theatre, although they are not exactly the same thing) go back thousands of years before anything came along that could be remotely assigned as ‘literature’. Probably, like dancing and chanting (a prelude to singing) the art of mimicry is among the earliest forms of expression to be hardwired into the human psyche. It should always be kept in mind that play-acting is essentially storytelling and just as the drawings on cave walls tell stories, so, one can safely assume, did the earliest body-swaying and vocal signaling rituals.

The antecedents of what became the modern stage began with the ancient Greeks, whose great playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides can still be enjoyed today -- either as performances, or more likely in written form to be studied by scholars. Much later, in Medieval times in Europe, such miming or play-acting, as it were, took place in the church, and in particular served as physical manifestations of virtues and vices, and as such can be labeled as allegories. Thus, characters acted out the themes of Prudence, Patience, Sloth, Avarice, and the like. Most importantly, their value was in being didactic, in instilling Christian values into those who observed them during the liturgy.

Performances of religious plays outside the church began sometime in the 12th century, during which time the shorter liturgical dramas merged into longer plays which were translated into vernacular and performed by laymen. By ‘vernacular’ is meant that they adapted the ‘script’ to a local brogue that could be understood and enjoyed by the people of that particular locale. Needless to say, none of this was written down into any lasting form.

The importance of the High Middle Ages in the development of theatre was the economic and political changes that led to the formation of and the growth of towns. In the British Isles, plays were produced in some 127 different towns during the Middle Ages. Probably the most important play during this period was called Everyman and enacted the story of a man who tries to flee death but is finally reconciled to it. Here is what it looked like in an early printed version:

EVERYMAN

Here beginneth a treatise how the High Father of Heaven sendeth death to summon every creature to come and give account of their lives in this world, and is in manner of a moral play.

MESSENGER

I pray you all, give your audience,

And hear this matter with reverence,

By figure of a moral play.

The Summoning of Everyman called it is,

That of our lives and ending shows

How transitory we be all day.

This matter is wondrous precious

But the meaning of it is more gracious

And sweet to bear away. The story saith:

Man, in the beginning

Look well and take good heed to the ending,

Be you never so gay!

Ye think sin in the beginning full sweet,

Which in the end causeth the soul to weep

When the body lieth in clay.

Here shall you see how Fellowship and Jollity,

Both Strength, Pleasure and Beauty,

Will fade from thee as flower in May;

For ye shall hear how our heavenly King

Calleth Everyman to a general reckoning.

Give audience and hear what He doth say.

These lines were performed by real actors on the stage, but we have the printed version which can be read: thus, the merger of drama and literature was underway.

Everyman (author unknown) bore little resemblance to later works during the fabled Elizabethan period in England when such masters as Shakespeare, Jonson, Marlowe, and Kyd wrote scripted pieces which, though recording them for posterity was not of paramount concern, these folios have survived and now are simply read as often as performed. It’s because they lend themselves to reading and, in some cases, even serve modern scholarship best as written documents instead of live performances -- which is to say that they stand as literature whether they are acted out onstage or not. How many modern students of literature have struggled with Shakespeare’s mighty lines in Hamlet, Lear, and Othello without ever actually having seen the plays performed? (Probably more than would like to admit it!)

Of course, these plays can be brought to life to great effect, and it is worth watching as Prince Hamlet worries and tries to chart the course of his revenge, rambling and disseminating even as Lear and Othello rage, as innocent Desdemona is put to death and Lady Macbeth unleashes her murderous, ambition-driven schemes. Nor can anyone even begin to deny that Marlowe and Shakespeare were great poets also. Shakespeare is as famed for his Sonnets as for the plays, and Marlowe’s great poem that starts, “Come live with me and be my love, and we will all the pleasures prove….” (‘The Passionate Shepherd to his Love’) is still recited at weddings today.

Queen Elizabeth I

The English theater owes a debt of gratitude to Queen Elizabeth I. Prior to her patronage, play acting was held in low esteem, the players thought to be vagabonds and ruffians, not unlike the circus performers of later centuries. They would go from town to town, throwing up impromptu stages which had no props nor anything resembling scenery, so the actors (and they were all men because no women were allowed to perform, it being thought highly unladylike) would put on some kind of show, often bawdy and full of low-life references but also melo-dramatic and stuffed with battles (whose setting had to be imagined although a great deal of half-choreographed, often violent sword-fighting went on in which people actually got hurt). Then the players would collect their pay from the audience, dismantle the stage, throw down a few pots of ale, and head to the next location. It was a hard life, but there was always an audience. Naturally, the church hated it. That would cause problems later on when the Puritans were running England in the period of Oliver Cromwell.

If not Elizabeth and her privy council the English theatre would never have produced lines like these (Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus -- here Paris speaking of Helen and the Trojan War:

“Was this the face that launch'd a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss.

Her lips suck forth my soul: see where it flies!

Come, Helen, come, give me my soul again.

Here will I dwell, for heaven is in these lips,

And all is dross that is not Helena.”

Nor these beautiful, elusive words from Shakespeare as he says farewell to the theatre in The Tempest:

Prospero speaks to Ferdinand and Miranda

“You do look, my son, in a moved sort,

As if you were dismay'd: be cheerful, sir.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp'd towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Ye all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. Sir, I am vex'd;

Bear with my weakness; my, brain is troubled:

Be not disturb'd with my infirmity:

If you be pleased, retire into my cell

And there repose: a turn or two I'll walk,

To still my beating mind.”

All of this, it goes without saying, can be rendered flawlessly on the stage, but anyone who is at all perceptive can see the majesty and beauty in the language. This therefore is literature put in motion. Most of the plays that were not performed directly in front of Elizabeth were conducted in an area just outside the city gates of London, a place called Southwark. In this way, the puritanical laws within the metropolis that would have shut the theatre down had no jurisdiction.

Several important historical events worked in the favor of drama on the paint stage as it entered the annals of genuine literature. The first of these has been the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1450; the second had come when John Wycliffe (later burned at the stake for his ‘heresy’) decided to translate the Holy Bible from Latin into English in order that people could read God’s words for themselves instead of having to rely on the self-serving explanations of rich bishops and cardinals.

These events were so significant because on the one hand they allowed for wide distribution and on the other (in Wycliffe’s case), most important book in all Christendom was suddenly available (although it was not as simple as that, due to mass illiteracy among the populace and the ferocious resistance on part of the monolithic Catholic Church). But, suffice it to say, that without the ability to print, all of Shakespeare would have been lost to us, as it very nearly was. Thus, due to the possibility of wide dispersal of literary material, the lines voiced from the painted stage could now be recorded for posterity.

A big setback for all this came when the English king was dethroned, and the grim period of Oliver Cromwell and the ‘Roundheads’ (due to their stark, cropped haircuts) in a Puritan regime known to us as “The Protectorate”. After supervising the beheading of King Charles in 1649, there followed a lengthy period of austere religious fervor which, of course, meant the temporary death of the theatre. One cannot help but notice that, while the Christian religion has given birth to some of the greatest art and literature the world has known, the more grim, narrow, and fanatical elements that have infested it and often seized control have been the authors of remarkable acts of brutality, superstition, and general stupidity. (The Olympic Games went begging for a thousand years because of Christians who were determined to banish such ‘paganism’ from their midst.) So down went the theatre until Cromwell died, the Protectorate was dismissed and a new king restored.

When order was re-established, albeit with Parliament running the show instead of the King or Queen (a formula which remains intact to this day), the stage came back, although it is difficult to insist that literature had much to do with it. The Neoclassical period was mostly ornamental and a rather artificial attempt to recover the glorious past of the Romans. Much of the writing and painting was decorous also. Thus, it is not until the mid-to-late 19th century that we again see a happy marriage between theatre and literature. British theatre experienced revitalization with the work of George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, John Galsworthy, William Butler Yeats, and Harley Granville Barker. Unlike most of the gloomy and intensely serious work of their contemporaries, Shaw and Wilde wrote primarily in the comic form. Edwardian musical comedies were extremely popular, appealing to the tastes of the middle class in the Gay Nineties and catering to the public's preference for escapist entertainment during World War I.

In the case of the individuals mentioned above, especially, Yeats, Shaw, and Wilde, great literature abounded, Yeats (who was Irish, as was Shaw) being recognized as perhaps the greatest poet of the 20th century.

In recent times, the theatre has become more and more experimental, and it could be argued that many of the scripts are not exciting as literature per se in that reading them does not bring them to life in the manner that they can be delivered onstage. Samuel Becket’s Waiting for Godot and the work of the Englishman Tom Stoppard would be good examples. Well, we live in minimalist times and most of the great scripts are in that way, devoid of the clever repartee and eloquence of the past.

Henrik Ibsen

Finally, it can be said that the stage worldwide as well as in Great Britain has been blessed by great writers of literature such as the Russian Chekov and the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. In America, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman revolutionized the theatre, and much of Edward Albee’s work “The Zoo Story” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf’ stand as examples of major literature as well as great drama scripts. T.S. Eliot, whose rank among the greatest poets of all time is monumentally secure, was born in America but moved to Britain and became a royal subject. His work Murder in the Cathedral about the martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket is likewise a literary masterpiece.

The world was given literature simultaneously with magnificent dramatic theatre with lines such as the following from Shakespeare himself:

“To be, or not to be: that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there's the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law's delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover'd country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.”

Surely, then, this is the best of both worlds: drama and literature.