NYT Students Editorial Contest 纽约时报中学生社论竞赛是纽约时报一系列学生写作竞赛之一,比赛邀请学生将对各类社会话题的想法变成正式的、简短的、以证据为基础的说服性文章,鼓励学生通过使用多种消息来源来拓宽自己的新闻渠道,了解对所选问题提供各种观点的消息来源。如果你:

- 关注社会时事热点

- 积极观察和探索世界

- 希望参加人文类竞赛

- 渴望提高自己的写作能力

- ……

那这个能让文理科生“爬藤”的赛事就非常适合你!第十届纽约时报中学生社论竞赛目前已开启申报提交,抓紧时间准备吧!

赛事基本信息

?适合对象:11-19岁的中学生

?比赛时间:作品提交截止日期:2023年4月12日

?参赛规则

1、选择一个你关心的话题(不管它是不是在纽约时报网站上讨论的话题)然后从《纽约时报》内外的来源收集证据,写一篇简明的社论;

2、所有引用需要注明出处,至少1处来自《纽约时报》过往文章,至少1处来自《纽约时报》所刊文章之外的可靠来源;

3、字数不得超过450词,所以要确保你的论点足够聚焦,并能提出一个强有力的理由。(请注意:标题和参考来源的字数,不计入450字的限制);

4、你可以自己独立一人写社论,也可以和一个小组一起写,但每个学生只提交一篇社论。

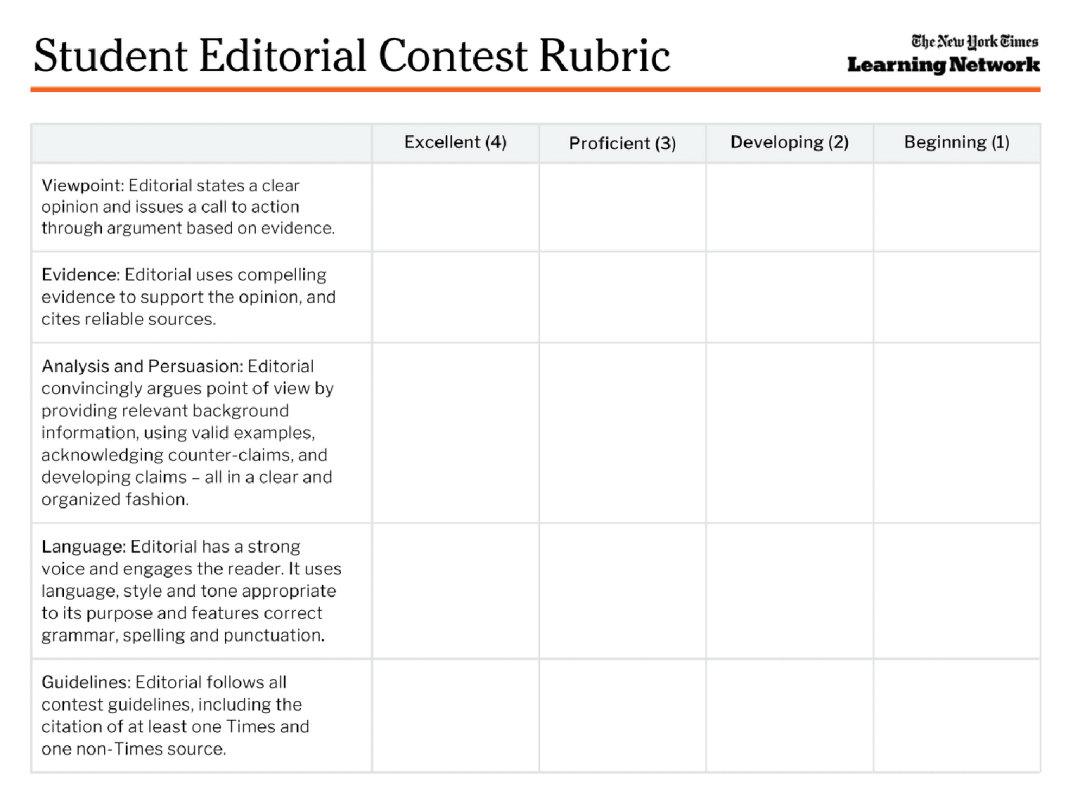

?评审标准

?奖项设置

三类奖项

-

Winners

-

Runnerup

-

Honorable mention

作为进入知名大学的关键助力项目,竞赛的意义越来越重要。同学们很有必要尽早准备类似纽约时报写作竞赛这样的国际竞赛,从而在大学申请时展示自己的社会参与度与学术发展潜力。 为更多对人文类竞赛感兴趣,有想法但苦于不知如何完美呈现的学生能够参与到这项赛事,缪思学霸导师特推出针对本次竞赛的一对一指导项目。

?招生对象:

11-19岁的中学生(必须)

?指导形式:

一对一讨论课(每节课50-60分钟)

课后指导:草稿修改、文章润色、最终定稿

?一对一指导课安排:

| 课次 | 上课内容 |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

?对标能力:

- 网络信息搜索

- 英语原版阅读(《纽约时报》难度级别)

- 对议题的思辨

- 通用写作:论点和论据,参考资料引用

- 说服性文章的写作

往年获奖文章分享,大家可以感受一下难度。

Endangered Languages Are Worth Saving

By The Learning Network

June 22, 2022

This essay, by Zoe Yu, age 17, from The Woodlands College Park High School in The Woodlands, Texas, is one of the Top 11 winners of The Learning Network’s Ninth Annual Student Editorial Contest, for which we received 16,664 entries.

We are publishing the work of all the winners and runners-up over the next week, and you can find them here as they post.

Endangered Languages Are Worth Saving

Every summer evening at 8 p.m. sharp, my grandma and I plant ourselves in front of the TV. Our next hour is filled with on-screen bouts of amnesia, plotting mothers-in-law, and tearful declarations of love in the rain. But what may seem like ordinary soap opera scenes are far more than melodrama and theatrics: Dialogued entirely in Taiwanese Hokkien, they’re artifacts of a once-dying language.

Linguists expect 90 percent of languages to become obsolete in the next century — and this mass extinction is no accident. Under colonial rule, learning or speaking my grandma’s native Hokkien, along with dozens of indigenous languages, was illegal by law. Schools were forbidden to teach using local dialects; formal institutions shifted to operate by the dominant Mandarin; and homegrown languages, stigmatized as coarse and improper through decades of repression by hegemonic language policies and imperialism, became a marker of backwardness. Today, more than half of native Hokkien speakers no longer use the language at home.

Unfortunately, this tragic silencing isn’t a rare practice. In the 1950s, thousands of Native American children were forced to surrender their mother tongues in boarding schools designed to eradicate indigenous identities. Even now, languages are vanishing at the hands of economic and social power struggles in which smaller communities are pressured to adopt the dominant language that governs work, entertainment and daily life. In fact, California repealed a law requiring “English-only” instruction just four years ago.

But shouldn’t we feel relief that we don’t live in the madness of a Tower of Babel society? While lingua francas undoubtedly streamline global communication, language isn’t solely a tool for business negotiations or celebrity gossip. Steeped in history and heritage, it’s a pillar of culture that built ancient empires, immortalized sacred religious texts, and stockpiled centuries of natural and medicinal wisdom. Records of past civilizations, together with poetry, music and folklore, hinge on a language’s grammatical and syntactic quirks.

The impact of language also spills beyond the past to influence ways of thinking in the present. Have you ever wondered why “death” is feminine in some paintings but masculine in others? It turns out that the gendering of nouns in an artist’s native language plays a role in how he or she decides to bring abstract concepts to life. Beyond art, researchers have also found links between language and perceptions of time, color and emotion.

Documentation projects and protective laws are already on the front lines in the battle against language death — but they won’t have a fighting chance until we realize that pruning a language tree kills more than just words. And if we don’t? Then, our rich forests of linguistic diversity will be flattened into barren wastelands, unable to support the cultures and peoples that once thrived within.

Works Cited

Boroditsky, Lera. “How Does Language Shape the Way We Think?” Edge.org, 11 June 2009.

Casey, Nicholas. “Thousands Once Spoke His Language in the Amazon. Now, He’s the Only One.” The New York Times, 26 Dec. 2017.

Gantt, Amy. “Native Language Revitalization: Keeping the Languages Alive and Thriving.” Southeastern Oklahoma State University.

Sandel, Todd L. “Linguistic Capital in Taiwan: The KMT’s Mandarin Language Policy and Its Perceived Impact on Language Practices of Bilingual Mandarin and Tai-gi Speakers.” Language in Society, 22 Oct. 2003.

Segel, Edward, and Lera Boroditsky. “Grammar in Art.” Frontiers in Psychology, 13 Jan. 2011.

Tesch, Noah. “Why Do Languages Die?” Encyclopedia Britannica.